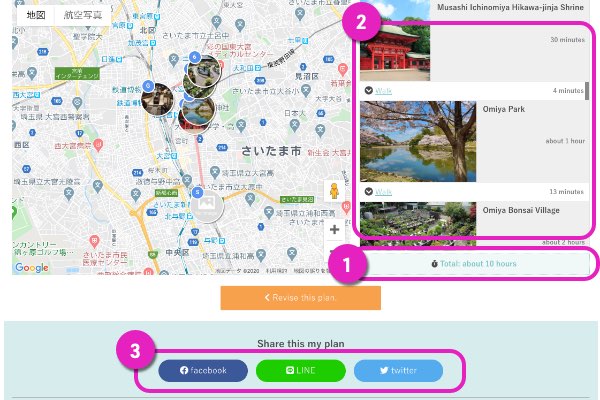

Learn more about the Omiya Bonsai Art Museum!

Bonsai and the Four Seasons

Sensitivity to the changing seasons is deeply embedded in the Japanese way of life. The country’s traditional calendar, used from ancient times up until the late nineteenth century, contained not only the familiar “four seasons” but a remarkable 72 “micro-seasons,” each subtly different from those preceding and following it. Awareness of such micro-seasons has for centuries manifested itself in a range of customs, cultural practices, and artistic forms. The arts of bonsai are very much a part of this tradition.

Bonsai artisans will often make use of seasonally shedding zoki trees or kusamono (lit., grass trees) when they wish to express something relating to the passing of the seasons, or a particular point in the year (such as New Year’s). To demonstrate just how dramatically the impression given by a zoki bonsai can change with the season, the Omiya Bonsai Art Museum’s Collection Gallery features an interactive display. By touching or swiping, the screen reveals how trees from a variety of popular species take on different guises through the year.

Iwashide (summer)

Iwashide (autumn)

Iwashide (winter)

Bonsai Display Rooms (Zashiki-kazari)

The Omiya Bonsai Art Museum is home to the world’s only dedicated exhibit showing how bonsai are displayed in three types of tatami-floored rooms traditionally used for entertaining guests in Japan. These interior styles and their associated modes of decoration, together known as zashiki-kazari, were inspired by Chinese calligraphy scrolls and formalized, according to social function, in the Muromachi period (1336–1573). By the late Edo period (1603–1868), during which time Chinese-style tea culture became popular, bonsai were incorporated into each style of room. Each type is authentically recreated at the museum, and although visitors are not allowed to cross the threshold into the rooms themselves, it is easy for them to imagine sitting inside on the tatami.

Bonsai were later additions to existing modes of interior decoration, but came to be their focal point or aesthetic anchor around which other items placed in the tokonoma alcove, such as hanging scrolls and mountain-like suiseki stones, are harmonized. From left to right, the three zashiki-kazari rooms are in the middle-ranked gyo style, which is the most common type of Japanese room seen today; the so style designed mainly for informal serving of tea; and the shin style, the most formal and intended for guests of high social status. As in the Collection Gallery, the bonsai displayed here are changed weekly.

Gyo style

So style

Shin style

Bonsai Garden

Here around 60 bonsai from the museum’s collection are displayed outdoors in an elegant Japanese-style garden replete with a boat-shaped central pond and a tranquil azumaya (arbor). The selection is ever-changing, being revised each week and regularly featuring some of the Omiya Bonsai Art Museum’s most treasured trees.

To truly appreciate a bonsai means giving it full, undivided attention, and the garden’s design encourages this: trees are displayed atop simple wooden plinths that do not distract from the bonsai themselves, and each exhibit is given plenty of breathing room. Depending on their design, certain bonsai are arranged so that they may be viewed from all angles. A Japanese white pine that is one of the largest bonsai in the collection, when out in the garden, is placed upon an equally sizable turntable that enables different parts of the tree to receive optimal sunlight as needed.

The full beauty of this garden is revealed when taken in as a whole: the museum’s second-floor terrace affords a full bird’s-eye view of the garden’s asymmetrical design. While photography is forbidden down in the garden itself, it is encouraged from this splendid vantage point.

Bonsai Terrace

The Bonsai Terrace, located on the second floor of the main museum building, makes an excellent vantage point from which to view the entire Bonsai Garden—the azumaya (arbor), boat-shaped central pond, and the 60-some bonsai displayed in the open air.

The Terrace is also a good spot for photographing the Garden, and is encouraged there, although visitors are asked not to take photographs in the garden itself. In the foreground is the elegantly asymmetrical design of the garden, attractively set against the contemporary architecture of the Collection Gallery and Exhibition Room buildings, and the verdant greenery beyond.

Visitors are encouraged to relax and enjoy the Bonsai Terrace. There is space for eating home-prepared picnic lunches and the museum’s free wi-fi is available.

Photography

In order to protect the delicate trees and also because the designs of certain bonsai are subject to copyright, the Omiya Bonsai Art Museum requests visitors to refrain from taking photos in the main exhibits and Garden. For the same reasons, photography is generally also prohibited at the neighboring bonsai nurseries. At the Museum, however, a dedicated area where photography is freely permitted is located on the east side. A frequently changing display of 20 trees presents bonsai chosen to be at their best for the season. These might include flowering species in spring and summer, for example, or evergreen shohaku bonsai that resonate with the winter season. It is also possible to photograph wide-angle views or panoramas of the garden itself from the museum’s second-floor Bonsai Terrace, and from within the lobby.

Famous Bonsai Not to Be Missed

Among the factors that contribute to a bonsai’s prestige and worth, three factors are key: the age of the tree; its shape or design; and its history and provenance. Of course, different trees resonate with different viewers and for various reasons, and discovering personal preferences is part of the pleasure of bonsai appreciation. Nevertheless, the Museum recommends visitors to be sure to visit its most famous bonsai, described below.

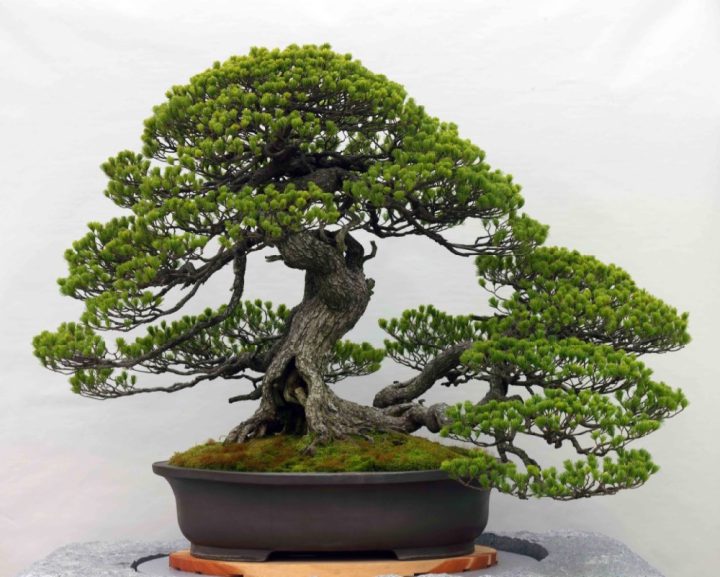

Goyomatsu (Japanese white pine) named “Chiyo no Matsu”

One of the largest bonsai in the collection, Chiyo no Matsu stands at 1.6 meters tall and has a width of 1.8 meters. A vast landscape is conveyed by branches that reach out along the horizon, while the shape of the tree as a whole suggests the billowing shape of the clouds of the Japanese midsummer.

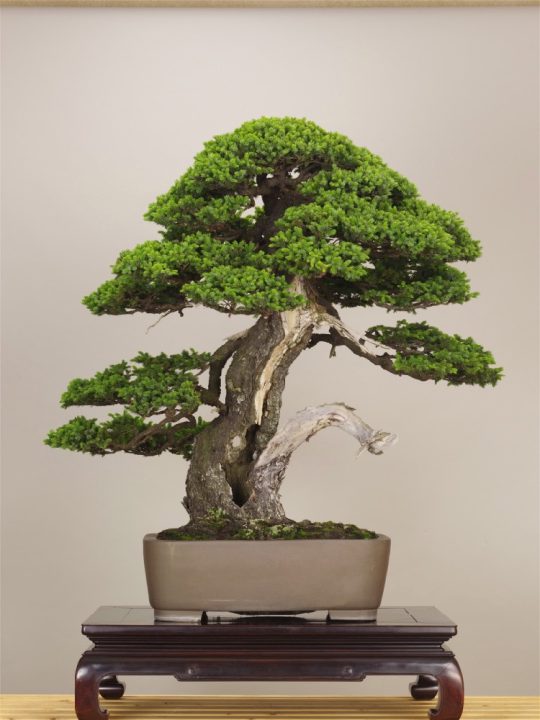

Ezo matsu (Ezo spruce) named “Todoroki”

Taken from the forests of Japan’s northernmost island Hokkaido (formerly known as Ezo) roughly a century ago, this oldest tree in the collection is around 1,000 years of age. It is believed to be one of the oldest spruce bonsai in the world.

Karin (Chinese quince)

The grandiose appearance of this roughly 150-year-old bonsai suggests the master of a magnificent forest, and possesses all the dignity of a fully-grown tree. Its impeccable lineage includes ownership by several notable figures, among them former prime minister Kishi Nobusuke (1896–1987). This tree was named the very first kicho bonsai (Bonsai of Cultural Importance) by the Japanese Bonsai Association in the 1980s.

Karin (spring)

This English-language text was created by Japan Tourism Agency.