Learn more about Omiya Bonsai Village!

History of Omiya Bonsai Village

Bonsai is an art form with centuries of history, but in Japan the arts of miniaturizing trees became increasingly popular around the turn of the twentieth century. Bonsai specialists in Tokyo sought greater space than was available to them in the cramped and crowded capital. Rapid industrialization, accompanied by rampant pollution, had made the city an increasingly unsuitable environment for cultivating sensitive “living artworks.”

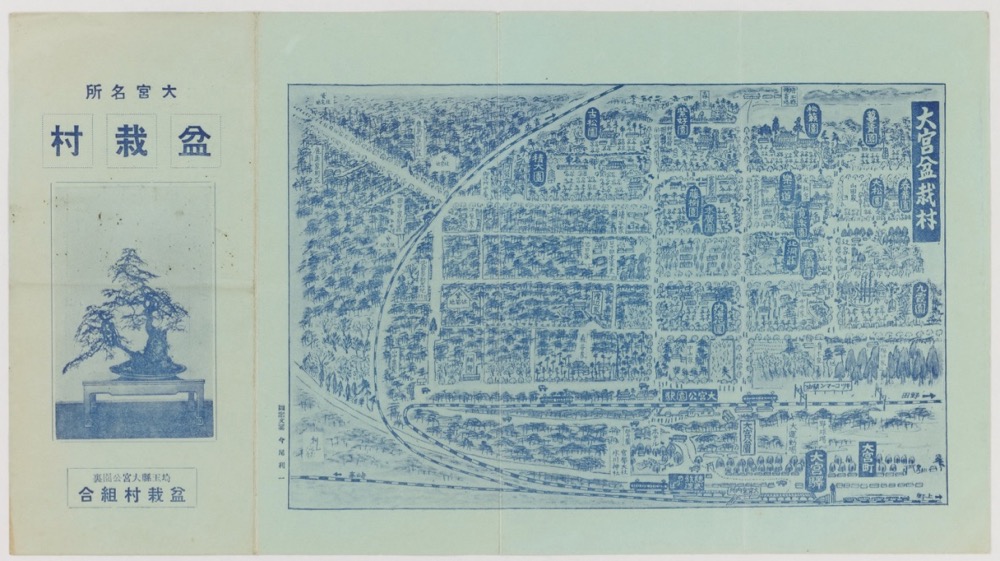

Omiya, a city in Saitama Prefecture, located 30 kilometers north of Tokyo, became a popular recreation spot with the opening of Omiya Park in 1885. A collective of Tokyo’s foremost bonsai artisans agreed that Toro, on the outskirts of Omiya, would make the perfect location for a village-like community of bonsai gardens. Environmental conditions were favorable in Omiya in those days, with cleaner air and better-quality groundwater than the rapidly growing capital. Another factor in Omiya’s favor was the soil. Debris from eruptions of Mt. Fuji in the distant past contributed to the area’s red clay earth, which had a low mineral content. Any flora planted in it would grow healthily, allowing for small amounts of the soil to be used for this art form centered on the miniaturization of nature.

Following the widespread fires and destruction of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, many bonsai artisans were even more eager to move away from the capital, and in 1925 Omiya Bonsai Village was established where it remains today. Previously underutilized land became a thriving hub of bonsai cultivation, providing a home for as many as 35 nurseries in the years leading up to World War II. Omiya Bonsai Village’s significance was acknowledged by the local government, which in 1942 officially named the district “Bonsaicho” (literally, “Bonsai town”).

The outbreak of war, however, led to a temporary decline in bonsai culture. The government-sanctioned anti-luxury movement deemed bonsai an indulgence, and many bonsai artisans were conscripted into the military. Most of Omiya Bonsai Village’s nurseries were forced to close. The few daring bonsai cultivators who remained continued their work in secret, through to the war’s end in 1945.

Japan’s postwar recovery and rise as an economic superpower that peaked with the “bubble economy” of the late 1980s paralleled the rising fortunes of both Omiya Bonsai Village and the art form itself. Omiya’s artisans worked to promote bonsai, through festivals and other means, and the trees became coveted possessions of wealthy politicians and businessmen. As Japan’s stature on the world stage grew, bonsai became internationally known, even symbols of the nation.

Today, with the economy no longer booming, bonsai has become a niche pastime. Throughout these changing times and into the twenty-first century, however, Omiya Bonsai Village has kept the art vibrant and internationally appreciated.

Internationalization of Bonsai

Bonsai is one of a handful of icons that signify Japan to the world. The journey to this emblematic status began in the late nineteenth century, as the country opened up to the world after more than two centuries of self-imposed isolation. At the world expositions, or expos where nations were showcasing their achievements in cultural, industrial, and other spheres, Japan was eager to put itself on the global map. Japan participated in the 1873 Vienna Expo to considerable acclaim, and five years later bonsai were presented as part of a Japanese garden built at the third Paris World’s Fair (1878). Few Europeans would have previously seen bonsai, including those who had traveled to Japan.

The fourth Paris World’s Fair (1889) made bonsai the talk of sophisticated Parisians, who were charmed by the trees loaned by some of Japan’s foremost private owners. This coincided with France’s “Japonisme” boom, in a country that is still today one of the most receptive to contemporary Japanese culture.

World War II temporarily dampened the pace of bonsai’s internationalization, but during the postwar recovery through the 1950s, the artisans of Omiya Bonsai Village worked to regain momentum. Their activities caught the attention of officers of the Allied Occupation, then began drawing politicians and dignitaries, both Japanese and foreign, to visit Omiya.

At the 1964 Tokyo Olympics an exhibition of bonsai was opened in Tokyo’s Hibiya Park for the 15-day duration of the games, introducing the art form to many foreign visitors. International awareness of bonsai was further expanded at the World’s Fair-style Expo ’70, held in Osaka. A major exhibition of bonsai was held throughout the six months of Expo ’70, presenting around 2,000 trees gathered from around Japan. In 1976, the word “bonsai” was added to the Oxford English Dictionary, confirming that this art form had truly entered the global consciousness.

The internationalization of bonsai continues into the twenty-first century. The World Bonsai Convention, first held in Omiya in 1989, draws enthusiasts in a different world city every four years and has been hosted by the United States, Germany, China, and other nations. As Japanese pop culture captures imaginations the world over, bonsai motifs appear on fashion catwalks and even in hairstyles, and the 2020 Olympics will likely further raise bonsai’s global profile.

The Bonsai Village Today

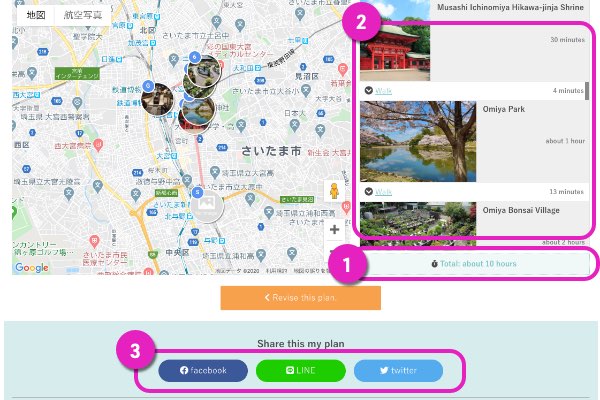

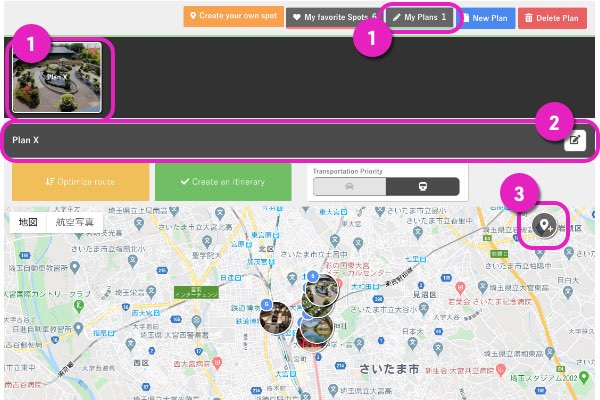

Almost a century since it was established, Omiya Bonsai Village continues to fulfill the vision of its founding artisans. What was once disused land on the periphery of town now thrives, in its own quiet and unhurried way, as Japan’s principal hub of bonsai culture. Seven dedicated bonsai gardens or nurseries, run mostly by second, third, fourth, and even fifth-generation artisans, cultivate and sell some of the most exquisite bonsai to be found in Japan. The nurseries also tend cherished bonsai on behalf of their owners, develop new techniques in the centuries-old art form, and spread awareness and knowledge through education.

Most of the bonsai gardens are within walking distance of each other and can be reached from either Toro Station (on the JR Utsunomiya Line) or Omiya Koen Station (Tobu Urban Park Line). Each garden offers a variety of bonsai species and designs, from modest to imposingly large in size. True bonsai aficionados, though, know that each Omiya bonsai garden is associated with a particular style or technique. This diversity is the produce of the healthy competition within the village-like community. Fuyo-en, for example, is famed for its seasonally changing zoki trees, while Kyuka-en, the second-oldest extant garden, is noted for its development of bonsai tools.

Despite the image bonsai has long held in Japan of being a pastime of the wealthy elite—understandable given the number of distinguished statesmen who have been bonsai lovers—at Omiya Bonsai Village small bonsai are available for as little as one thousand yen.

In addition to the village itself, local bonsai-related attractions include a seminar room and rest area named Bonsai Shiki no Ie (Bonsai House of the Four Seasons), and of course the Omiya Bonsai Art Museum which works closely with the bonsai gardens. A highlight of the year is when the gardens come together in May to present the Bonsai Festival.

Also nearby and worth seeing are the Uetake Inari Shinto shrine, location of a monument dedicated to Shimizu Ritaro (1874–1955), a key figure in the establishment of Omiya Bonsai Village; and the Manga Kaikan museum at the former atelier of manga artist Kitazawa Rakuten (1876–1955).

The path to the present day has not always been smooth for the Omiya Bonsai Village: the difficulties of the past and challenges it faces today closely parallel those of Japan itself. In the pre-World War II years there were some 35 bonsai gardens before wartime circumstances forced the majority of them to close. After the war, bonsai artists revived their profession as the nation grew into an economic powerhouse. In the twenty-first century, declining growth of both the economy and the population have had serious implications for the bonsai industry, with the number of bonsai practitioners showing a clear decrease. Nonetheless, bonsai is truly a labor of love for Omiya’s bonsai artisans, assuring the continued vitality and relevance of this horticultural art form.

This English-language text was created by Japan Tourism Agency.